Ask an Expert: Is Mandating Treatment Necessary or Helpful?

03/06/2023

Caleb Banta-Green, PhD, MPH, MSW

Director, UW Center for Community-Engaged Epidemiology, Education, and Research (CEDEER)

Substance use-related health services are a well-researched area. Many people, however, have outdated understandings of substance use and “substance use disorder” (addiction) and also don’t know much about what truly motivates someone to seek services to reduce the harms associated with their substance use.

Policymakers and others sometimes talk about the need for “mandated” treatment, when a person is required to attend a treatment program for their substance use instead of being sentenced to incarceration or other legal penalties for a crime.

But is mandating treatment necessary? What motivates someone to seek services for their substance use, what keeps them engaged in those services, and what does success look like?

What is “treatment” and how do we measure “success”?

Many people think of treatment for substance use disorders as “detox” and inpatient or outpatient care that usually includes counseling with a goal of complete abstinence from substance use (i.e., not using any substances at all anymore).

Yet over the past 20+ years, the idea of “treatment” has expanded to include different types of counseling supports, highly effective treatment medications like buprenorphine and methadone, health care more generally, and even social supports like housing assistance.

After years of being offered mostly in specialty addiction care settings (settings that only offer addiction treatment), addiction treatment has begun to expand to primary care and other medical settings (Simon et al, 2017) and, in the past few years, to community-based organizations, like syringe services programs, as well (Hood et al, 2020; Snow et al, 2019; Banta-Green et al, 2022).

This expansion of treatment services into other settings, and the addition of a broader array of services, comes as we align what we call “treatment” with our definition of “recovery.”

Our understanding of recovery has changed over time, as research in this area has expanded.

Previously, addiction treatment programs, particularly those programs mandated by the court system, had a required goal of complete abstinence. If that goal wasn’t met, the person was considered to have “failed.” In the context of treatment mandated by drug courts or other legal processes, that could mean criminal consequences, including jail or prison time.

We now know that relapses, or returns to substance use, are the norm for people recovering from a substance use disorder (Kelly et al, 2019). Returning to use doesn’t mean the person has “failed” treatment and needs punishment to motivate them to try harder – instead, it means they need more intensive care or different supports, including physical or mental health care and social services.

Extensive research shows that for people with a substance use disorder involving opioids or stimulants, recovery can take an average of 2-3 years (Kelly et al, 2019; Kelly et al, 2018) and often includes some amount of ongoing or intermittent substance use.

That’s why major organizations like the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s have a definition of recovery that focuses on improving functioning, not necessarily stopping all substance use: recovery is “a process of change through which individuals improve their health and wellness, live a self-directed life, and strive to reach their full potential.”

Both the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) also recognize that abstinence is not the only appropriate goal for the treatment of substance use disorders (Williams, 2018; Volkow, 2022).

Given all this, treatment programs that use abstinence as the only measure of success set people up for failure and, in the context of mandated treatment, take them off the path to recovery and put them on the path to legal punishment instead.

What motivates people to seek treatment and stay engaged with care?

There are many assumptions about what motivates someone with a substance use disorder to seek treatment, including the myth that many people who use substances don’t want help in the first place.

Based on surveys we’ve done with people who use syringe services programs (SSPs), people who use drugs – whether or not they have a substance use disorder – very often want drug-related health services to prevent injury, infectious disease, or death. These services are sometimes referred to as “harm reduction,” and they are often provided by SSPs, health departments, and other organizations.

Harm reduction services are supported by decades of research and are endorsed by federal agencies like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Javed et al, 2020) and the Department of Health & Human Services (HHS site), as well as professional organizations like the American Medical Association (Robeznieks, 2022).

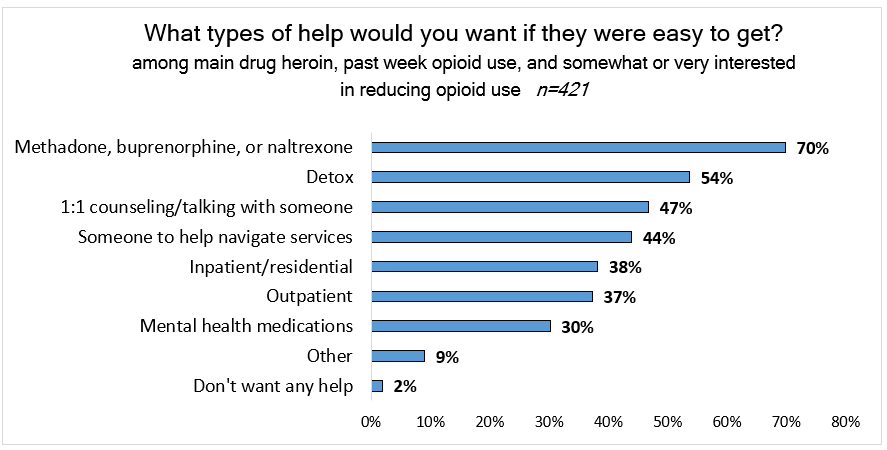

According to our surveys, of people whose main drug is heroin, 80% who inject say they want to stop or reduce their use. (Banta-Green et al, 2020). People want to change their harmful health behaviors – they just need the right kind of support to do it.

70% of these same people say they are most interested in opioid use disorder treatment medications, like buprenorphine and methadone, and nearly half are interested in other services, like care navigation, mental health counseling, or other types of addiction treatment.

Despite this clear interest in getting help with their substance use, however, 59% of people who needed health care in the prior year did not receive it, most often because of previous negative experiences with health care providers (Banta-Green et al, 2018).

That’s why offering low-barrier services at harm reduction sites in the community, like syringe services programs, could be highly effective in both supporting people to start care and keeping them engaged in that care long-term, whether it’s actual addiction treatment or other types of health or social services.

As one client told us, “I don’t need help quitting drugs per se, but I do need help with housing and health care to stay off the drugs” (Kingston & Banta-Green, 2016).

Is mandating treatment necessary or helpful?

It’s widely believed that the threat of criminal sanctions deters criminal behavior. However, when it comes to drug possession driven by substance use and use disorder, this theory is not supported by the science.

The Pew Charitable Trust conducted an analysis that found, in summary, that there is “no statistically significant relationship between state drug imprisonment rates and three indicators of state drug problems: self-reported drug use, drug overdose deaths, and drug arrests. […] These findings reinforce a large body of prior research that cast doubt on the theory that stiffer prison terms deter drug use, distribution, and other drug-law violations. The evidence strongly suggests that policymakers should pursue alternative strategies that research shows work better and cost less” (Pew, 2018).

One of the criteria for a diagnosis of “substance use disorder” is “Continued use of the substance despite it causing significant social or interpersonal problems” (DSM-5; APA, 2013). People with substance use disorders often experience a range of problems related to their substance use and many have suffered the consequences of the criminal legal system too.

For example, almost half of the people we interviewed at syringe services programs had been incarcerated in the previous year, and this incarceration was significantly associated with an increased risk of overdose (Jenkins et al, 2011).

Research consistently shows that being in jail or prison is dangerous for people who use drugs and greatly increases the risk of death from overdose (Binswanger et al, 2013).

Taken together, this means that criminal sanctions for substance use do not motivate people into seeking treatment and ultimately do more harm than good.

Though some research has found that drug courts, in which someone is sent to treatment instead of jail or prison, under supervision of a court/judge, have somewhat better outcomes than incarceration (Gottfredson et al, 2006), the strength of the studies so far is quite weak (Fischer, 2003). Some of the modest data looking at whether the threat of greater consequences impacts treatment retention or completion has found that it generally does not (Hepburn & Harvey, 2007).

Policymakers and community members often say that we need laws to force people into treatment for their own good, yet we already have legal tools to mandate treatment in extreme cases, such as involuntary treatment statutes. There is no data that supports using the criminal legal system as the default in simple possession cases to improve people’s recovery from substance use disorder.

What would work better? Health Engagement Hubs: The big front door to care people want to enter

Since most people who use substances have expressed an interest in receiving services related to their substance use, the development of community “Health Engagement Hubs” is one way we could expand availability of these services, help people reduce harms associated with their drug use, and, for those who are interested, help support recovery from substance use disorder (WA HCA, 2022).

Syringe services programs (SSPs) are already well-established community-based sites where people who use drugs can receive a wide range of supportive health services. These programs would be natural locations to serve as Health Engagement Hubs and would essentially create a big new “front door” into care that many people who use drugs would want to enter.

SSPs provide walk-in, same-day access to low barrier services like (Kingston, 2023):

- Minor wound care with triage and referral for more acute medical conditions

- Screening (and in some cases treatment) for HIV, viral hepatitis, and sexually transmitted infections

- Referrals for primary and specialty care, including substance use disorder treatment

- Medications for substance use disorder, like buprenorphine or methadone

- Screening, care coordination, and medication management for common mental health conditions

- Drop-in emotional support and brief harm reduction counseling

- Care navigation and case management

Many SSPs would like to provide medical, mental health, and substance use services like these, but need sufficient and sustainable funding to do so. To learn more about the services that SSPs across Washington State currently offer and would like to offer, check out our 2023 report, Overview and Perspectives of Syringe Services Programs in Washington State.

Conclusion

Despite the persistent belief that most people need to be forced into treatment for their own good, national research along with local data show this not to be the case. Conversely, providing a broad array of services to promote the health and well-being of people who use drugs is highly desirable to them and associated with engagement and positive outcomes.

Making these services available in community-based organizations that already provide a welcoming environment and have positive working relationships with people who use drugs is a way to quickly build a system of care that provides something for everyone, every day.

References

Need help getting a copy of any of the articles below? Email Meg Brunner for assistance!

- American Psychiatric Association. DIAGNOSTIC AND STATISTICAL MENTAL DISORDERS (DSM-5). APA, 2013. doi: 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

- Banta-Green CJ, Owens MD, Williams JR, et al. The Community-Based Medication-First program for opioid use disorder: a hybrid implementation study protocol of a rapid access to buprenorphine program in Washington State. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2022;17(1):34. doi:10.1186/s13722-022-00315-4

- Banta-Green C, Newman A, Kingston S. Washington State Syringe Exchange Health Survey: 2017 Results. Seattle, WA: Addictions, Drug & Alcohol Institute, University of Washington, January 2018.

- Binswanger IA, Blatchford PJ, Mueller SR, Stern MF. Mortality after prison release: opioid overdose and other causes of death, risk factors, and time trends from 1999 to 2009. Annals of internal medicine. 2013;159(9):592-600. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-159-9-201311050-00005

- Fischer B. `Doing Good with a Vengeance’: A Critical Assessment of the Practices, Effects and Implications of Drug Treatment Courts in North America. Criminal Justice. 2003;3(3):227-248. doi: 10.1177/14668025030033001

- Gottfredson DC, Najaka SS, Kearley BW, Rocha CM. Long-term effects of participation in the Baltimore City drug treatment court: Results from an experimental study. J Exp Criminol. 2006;2(1):67-98. doi:10.1007/s11292-005-5128-8

- Hepburn JR, Harvey AN. The Effect of the Threat of Legal Sanction on Program Retention and Completion: Is That Why They Stay in Drug Court? Crime & Delinquency. 2007;53(2):255-280. doi:10.1177/0011128705283298

- Hood JE, Banta-Green CJ, Duchin JS, et al. Engaging an unstably housed population with low-barrier buprenorphine treatment at a syringe services program: Lessons learned from Seattle, Washington. Substance Abuse. 2020;41(3). doi:10.1080/08897077.2019.1635557

- Javed Z, et al. Syringe Services Programs: A Technical Package of Effective Strategies and Approaches for Planning, Design, and Implementation. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2020.

- Jenkins LM, Banta-Green CJ, Maynard C, et al. Risk factors for nonfatal overdose at Seattle-area syringe exchanges. Journal of Urban Health. 2011;88(1):118-128. doi:10.1007/s11524-010-9525-6

- Kelly JF, Greene MC, Bergman BG. Beyond Abstinence: Changes in Indices of Quality of Life with Time in Recovery in a Nationally Representative Sample of U.S. Adults. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2018;42(4):770-780. doi:10.1111/acer.13604

- Kelly JF, Greene MC, Bergman BG, White WL, Hoeppner BB. How Many Recovery Attempts Does it Take to Successfully Resolve an Alcohol or Drug Problem? Estimates and Correlates From a National Study of Recovering U.S. Adults. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2019;43(7):1533-1544. doi:10.1111/acer.14067

- Kingston S. Overview and Perspectives of Syringe Services Programs in Washington State. Seattle, WA: Addictions, Drug & Alcohol Institute, University of Washington, February 2023.

- Kingston S, Banta-Green C. Results from the 2015 Washington State Drug Injector Health Survey. Seattle, WA: Addictions, Drug & Alcohol Institute, University of Washington, February 2016.

- Pew Charitable Trust. More Imprisonment Does Not Reduce State Drug Problems. Published March 8, 2018.

- Robeznieks A. Harm-reduction efforts needed to curb overdose epidemic. AMA website, Nov. 15, 2022.

- Simon CB, Tsui JI, Merrill JO, Adwell A, Tamru E, Klein JW. Linking patients with buprenorphine treatment in primary care: Predictors of engagement. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2017;181:58-62. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.09.017

- Snow RL, Simon RE, Jack HE, Oller D, Kehoe L, Wakeman SE. Patient experiences with a transitional, low-threshold clinic for the treatment of substance use disorder: A qualitative study of a bridge clinic. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2019;107:1-7. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2019.09.003

- US HHS. Overdose Prevention Strategy. US Department of Health & Human Services website.

- Volkow N. Making addiction treatment more realistic and pragmatic: The perfect should not be the enemy of the good. Nora’s Blog (director of NIDA), NIDA website, January 2022.

- Washington State Health Care Authority (WA HCA). Substance Use and Recovery Services Plan Recommendation. WA HCA, 2022.

- Williams AR. After many years, the FDA announces loosened standards for addiction medication approval. Health Affairs Forefront 2018. doi: 10.1377/forefront.20180320.58853