Read the full report here. A summary of the report, suitable for a general audience, is also available. Check out the interactive Prezi.

Unmet Needs, Complex Motivations, and Ideal Care for People Using Fentanyl in Washington State: A Qualitative Study

Report by Teresa Winstead, PhD, MA; Alison Newman, MPH; Everett Maroon, MPHc; Caleb Banta-Green, PhD, MPH, MSW

This report describes the responses to qualitative interviews with 30 people in Washington State who use fentanyl.

Responses reveal that fentanyl use exacerbates and complicates the gap between what people want and need and what is available to support their health. For many interview participants, continued fentanyl use was described as a rational response to the combination of their social reality and their practical access to care. Current systems of care around housing, behavioral health, medical services, or first responder services, were not designed with the potency, risk of overdose, and robust withdrawal symptoms of a substance like fentanyl. Right now, medical treatment for pain and support to address opioid dependence are more difficult to access than unregulated fentanyl.

Key Points

- Interview participants discussed the rapid change in the drug supply from heroin to fentanyl and how this affected their substance use.

- Almost all interview participants smoked fentanyl; a few also injected it. Many interview respondents had previously injected heroin and switched to smoking fentanyl due to fentanyl’s potency and the perceived lower overdose risk from smoking.

- Participants reported complex motivations for using fentanyl including physical pain, mental health issues, trauma, homelessness, opioid use disorder, and easy availability of fentanyl. The majority of respondents were unhoused for whom meeting basic needs like housing, food, and employment were a priority.

- For many respondents, the central benefit of using fentanyl was its ability to control their severe, chronic pain (70% of respondents mentioned pain management). Some participants started using fentanyl after a health care provider terminated an opioid prescription or they used fentanyl to self-medicate pain not otherwise addressed through a health care provider.

- The majority (70%) of participants were interested in reducing or stopping their fentanyl use. However, people expressed many barriers to doing so, including unavailable services, being unaware of what might work, fear of withdrawal, and challenges accessing and staying on medications like buprenorphine or methadone.

- When asked about the “ideal place” to receive medical care and/or help with substance use, people described holistic and individualized care that was affordable and easy to access. Specific services of interest included: programs to help meet basic needs, medical care, mental health care, care navigation, and support from people with lived experience of substance use.

- Many respondents were interested in or had previous positive experiences with methadone or buprenorphine for opioid use disorder. However, administrative and other barriers limited access to these medications. The regulations for dispensing methadone and the need for daily dosing were particularly challenging, especially for respondents experiencing housing insecurity.

- The combination of healthcare barriers, social determinants of health, the strength and half-life of fentanyl, and individual physical and mental pain produce a significant challenge for care systems to respond to the complex needs of many people who use fentanyl.

Background and Methods

Opioid overdose deaths in Washington State continue to rise and are primarily driven by unregulated fentanyl. From 2019-2022 the opioid overdose death rate in Washington State more than doubled from 11.3/100,000 to 24.9/100,000, and most of that increase was due to fentanyl. In 2022, fentanyl was involved in 90% of opioid overdose deaths in Washington State and 65% of all overdose deaths (see Drug-caused deaths across Washington State). The emergence—and now dominance—of fentanyl over heroin as the primary opioid in the illicit drug supply has changed the context of opioid use, increased overdose risk, and intensified the need for social and medical supports.

To contribute to this understanding, staff at the Addictions, Drug & Alcohol Institute (ADAI) conducted a qualitative study of people who use fentanyl to explore their experiences and views on the following topics:

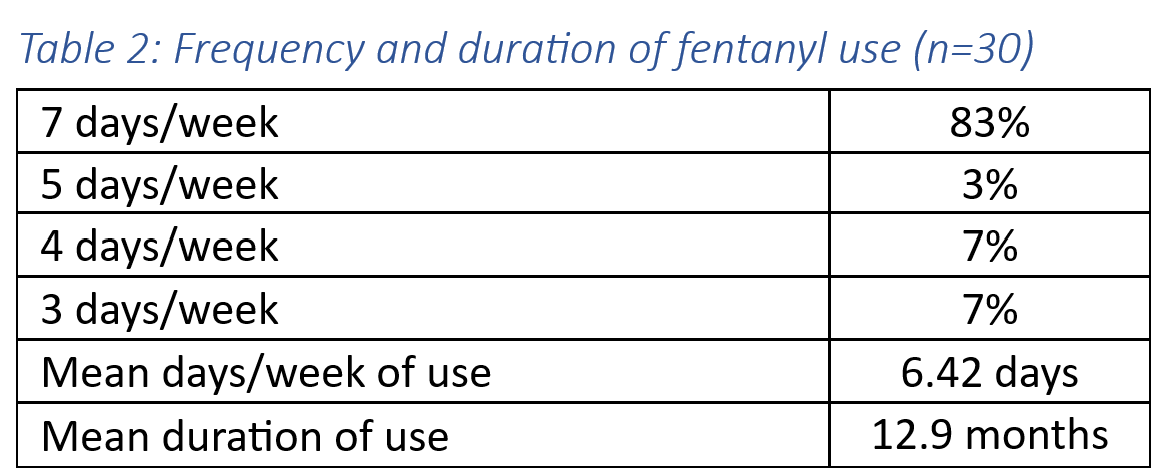

- fentanyl use patterns,

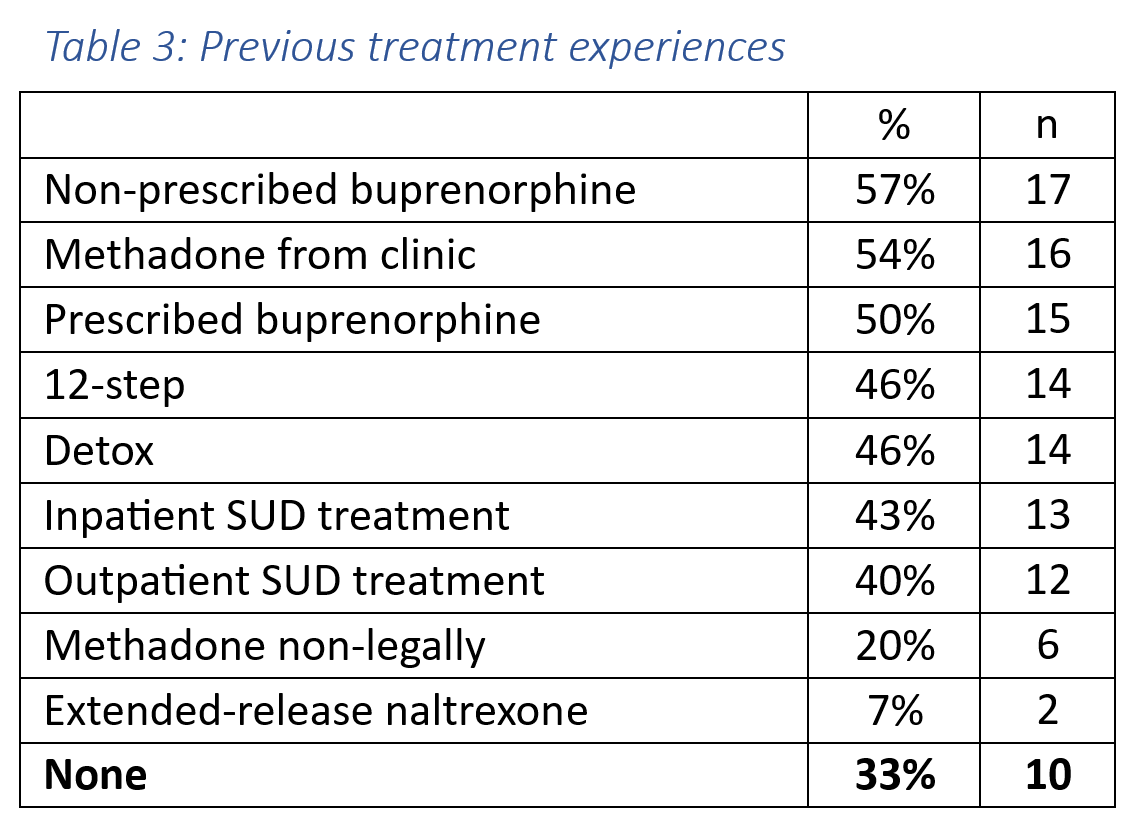

- previous treatment experiences,

- benefits and drawbacks of fentanyl use,

- interest in stopping or reducing fentanyl use, and

- preferred services and ideal care (including staff, services, location, and atmosphere.

This work builds on previous collaborations between ADAI and WA State syringe services programs (SSPs) including the bi-annual survey of SSP participants and two earlier qualitative interview projects. This exploratory qualitative study involved in-depth semi-structured interviews exploring the range of topics related to fentanyl use and access to care mentioned above. Interviews were conducted from September through October 2022, in collaboration with four WA State SSPs at five locations: Clallam County Harm Reduction Health Center in Port Angeles, Dave Purchase Project in Tacoma (two sites), Thurston County Syringe Services Program in Olympia, and Spokane Regional Health District Syringe Services Program in Spokane.

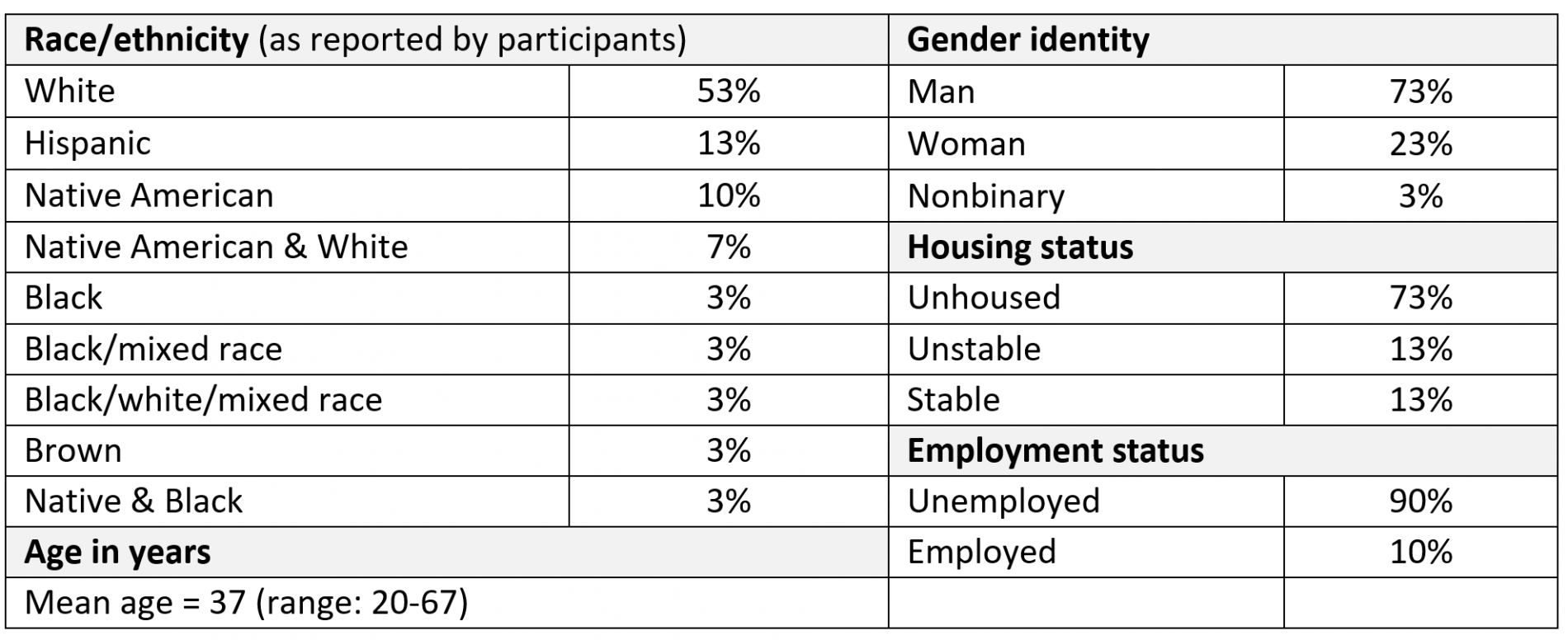

Demographics (30 participants)

Qualitative Themes and Findings

Recommendations

- Treat fentanyl as a serious public health crisis. Services and supports to reduce overdose risk and support people who use fentanyl should be expanded immediately in order to save lives.

- Ask people who use fentanyl what services and supports would help them. People who use fentanyl are experts on their lives and can provide key insights into barriers and facilitators for improving their health and expanding life opportunities.

- Build and support accessible programs that focus on health. Programs should have accessible locations and hours, and be flexible to meet participants’ diverse needs. These needs include physical and mental health, and for many people, serious chronic pain. Programs should include harm reduction approaches, services like safer smoking and overdose prevention supplies, and staffing facilities with nonjudgmental staff who understand the challenges individuals facing related to substance use.

- Meet people’s basic needs. Social determinants of health are drivers and exacerbators of fentanyl use. Programs should address people’s basic needs without making it contingent upon their level of interest in stopping their substance use.

- Provide safer smoking supplies to engage people who use fentanyl. Most of the people we spoke with smoked fentanyl, and perceived benefits to smoking over injecting. Distribution of safer smoking supplies is a key way to engage people who use fentanyl.

- Increase accurate information and education about methadone and buprenorphine. People are interested in these life-saving medications but misconceptions about their efficacy and difficulty keep people from starting or staying on them.

- Consider safe supply. Fentanyl is particularly deadly due to its potency and its variability. The people we spoke with wanted to stay alive, took steps to reduce their risk of overdose, and did not like that fentanyl was highly variable. Providing a source for regulated, quality-consistent opioids (other than MOUD) may be able to help decrease overdose deaths and provide some stability for people who use fentanyl.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the syringe services program participants who shared their time, expertise, and experiences with us. Your insights and knowledge are essential to guide the work to reduce overdose deaths and improve the health of people who use drugs.

Thank you to the syringe services programs who partnered with us on this project: Clallam County Harm Reduction Health Center; Dave Purchase Project in Tacoma; Thurston County Syringe Services Program in Olympia; and the Spokane Regional Health District in Spokane. These interviews were possible thanks to the trust and positive relationships you have with your participants. We appreciate the work you do to keep people alive.

Everett Maroon was involved in this project as part of his practicum with the University of Washington School of Public Health. Everett was supervised by Alison Newman, with Caleb Banta-Green as the practicum faculty advisor.