“I Think One Enhances the Other”: Use of Harm Reduction & Drug Treatment Among Participants of Syringe Services Programs

Alison Newman, MPH; Teresa Winstead PhD, MA; Leif Layman, MPH

Full report | Participant summary | Webinar recording

Key Findings

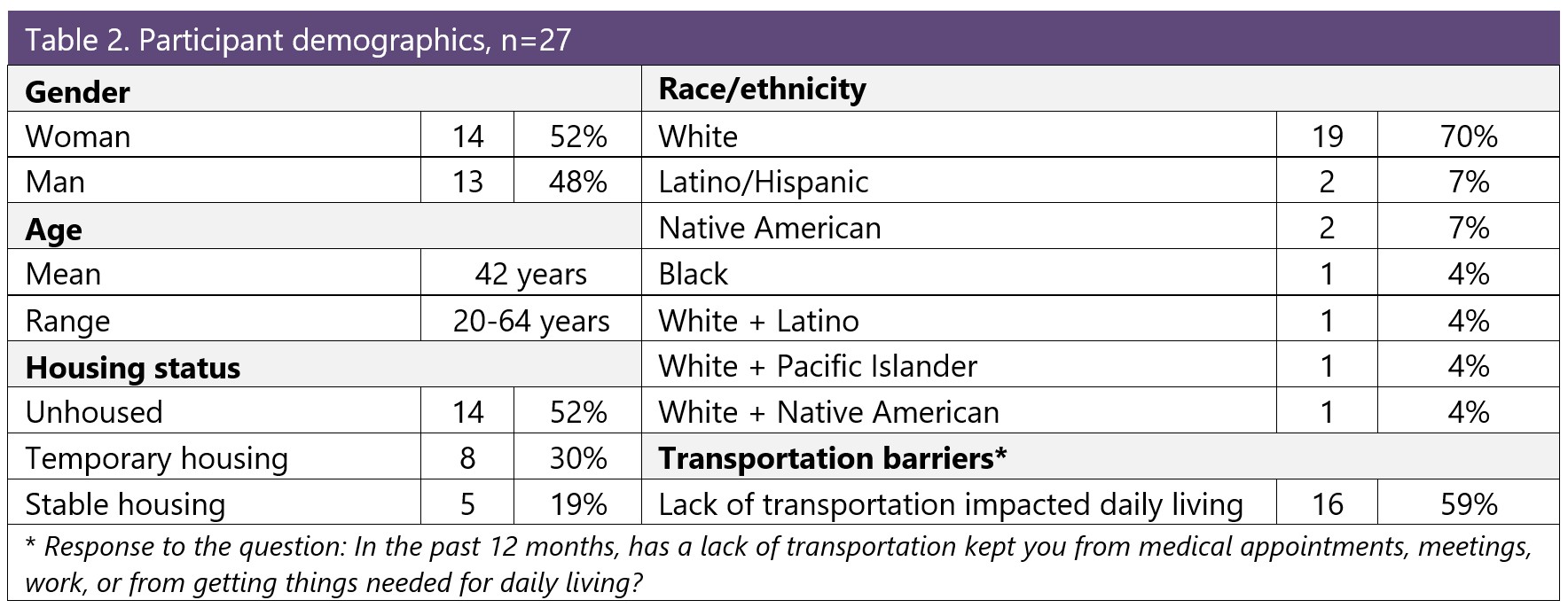

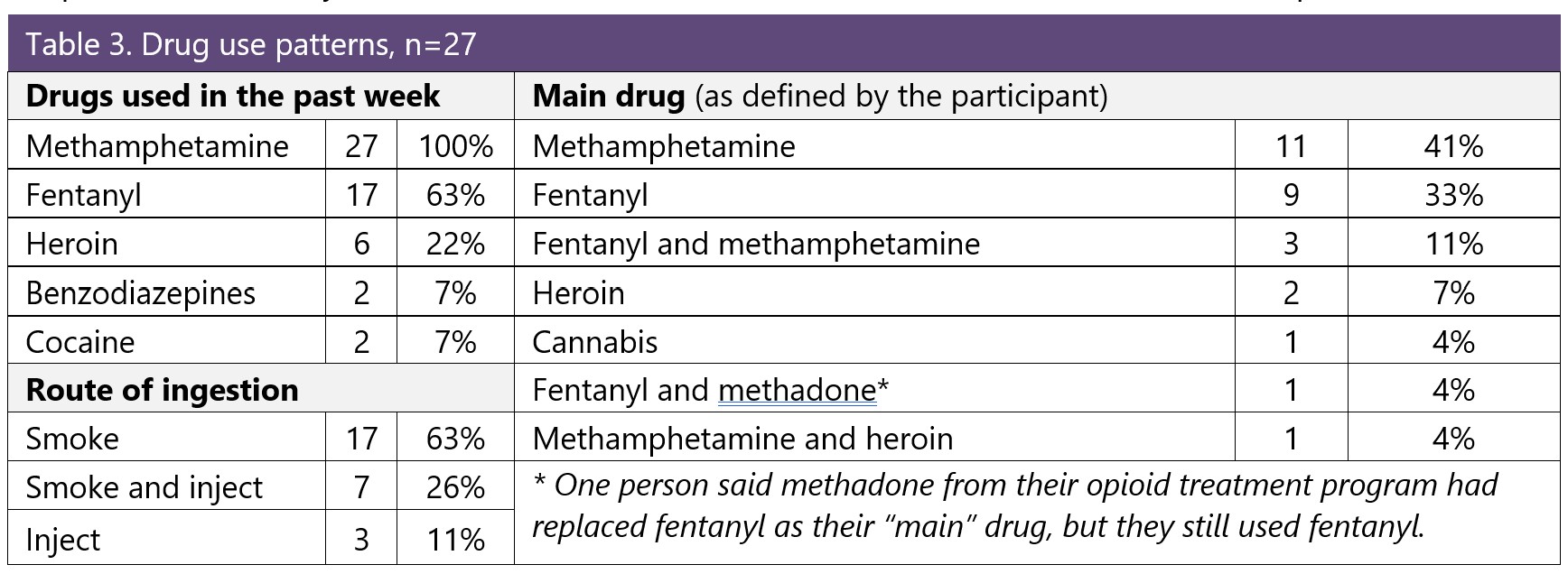

- Interviews were conducted with 27 participants of three syringe services programs (SSPs) in WA State; all had recent experience with substance use disorder (SUD) treatment.

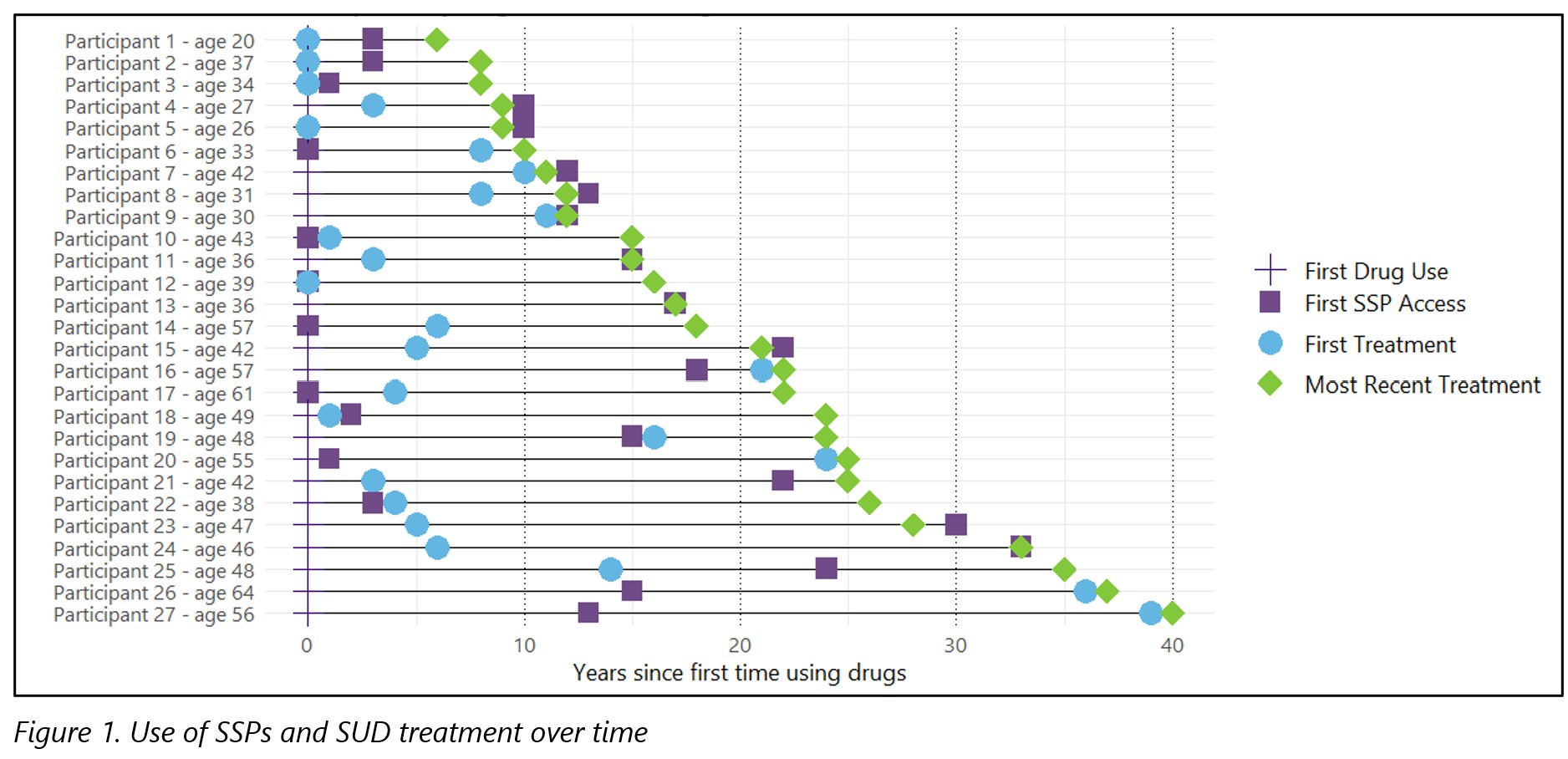

- Participants had used both SSPs and SUD treatment, sometimes concurrently. SSPs were often important access points for harm reduction services before, during, and/or after SUD treatment.

- The positive aspects of SSPs for participants included their easy access, friendly staff, and availability of supplies to meet basic needs and reduce health risks of drug use.

- The benefits of SUD treatment for participants included reduced drug use, better coping skills, and improved quality of life. However, participants also reported challenges in accessing or staying in treatment or finding programs that were a good fit.

- Most interviewees valued access to both harm reduction and SUD treatment concurrently, though some reported challenges using these services simultaneously.

- More than half the participants were interested in receiving treatment at an SSP due to the easy access and supportive staff.

Background

People who use drugs access different types of services to manage their health and substance use. These can include medical and mental health care, substance use disorder (SUD) treatment, and harm reduction services, most often provided by syringe services programs (SSPs)*. SUD treatment can include detox services, inpatient/outpatient treatment, medications prescribed for opioid use disorder (e.g., methadone, buprenorphine, naltrexone) or recovery support groups.

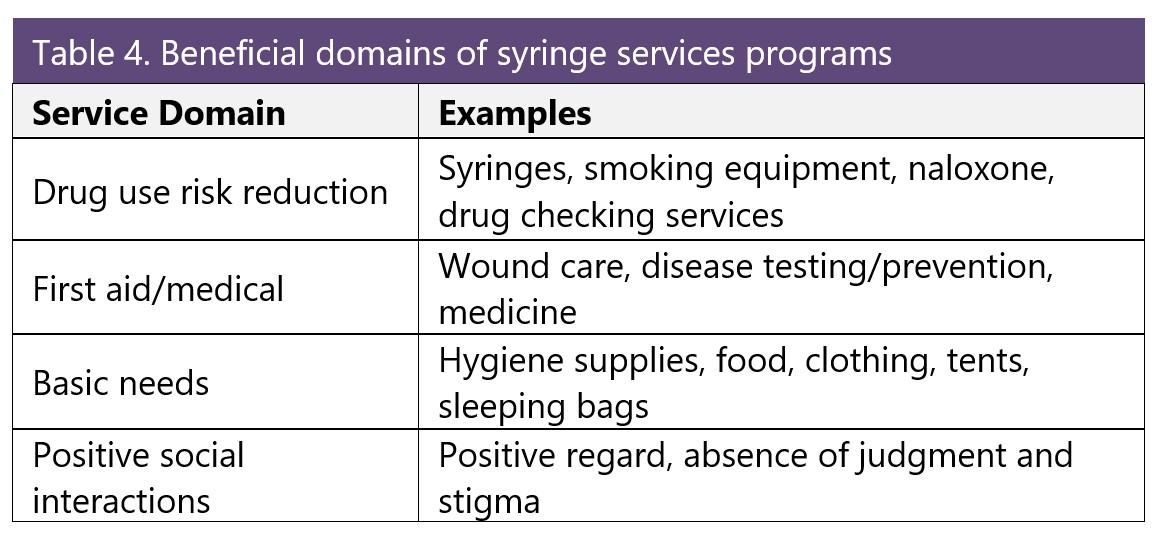

SSPs provide education, materials, and services to reduce risks of illicit drug use (e.g., sterile syringes and/or smoking equipment, naloxone, wound care supplies); address other health needs (e.g., nicotine replacement therapy, contraception, condoms); or fill basic needs (e.g., tents, food, clothing). Services and supplies vary by program, but all SSPs offer referrals to local services and SUD treatment. Learn more about WA State SSPs here.

Traditionally, the realms of harm reduction and drug treatment have often been seen (by providers and individuals) as siloed and mutually exclusive, given their different roles and orientations on abstinence. For many people who use drugs, however, these two worlds are often less distinct and may even overlap at times. This study aimed to understand the range of SSP participant perspectives about their use of harm reduction services and SUD treatment.

*“Syringe services programs” (formerly known as “needle exchanges”) provide education, materials, and services to support safer use of illicit drugs. From their inception, these programs have focused on injection drug use. But many now also provide supplies for safer smoking of drugs to engage people who do not or have never injected drugs. Because of this broader reach, some SSPs prefer to call themselves “harm reduction programs“ or “harm reduction centers.” For consistency, this report uses the term syringe services programs.

Methods

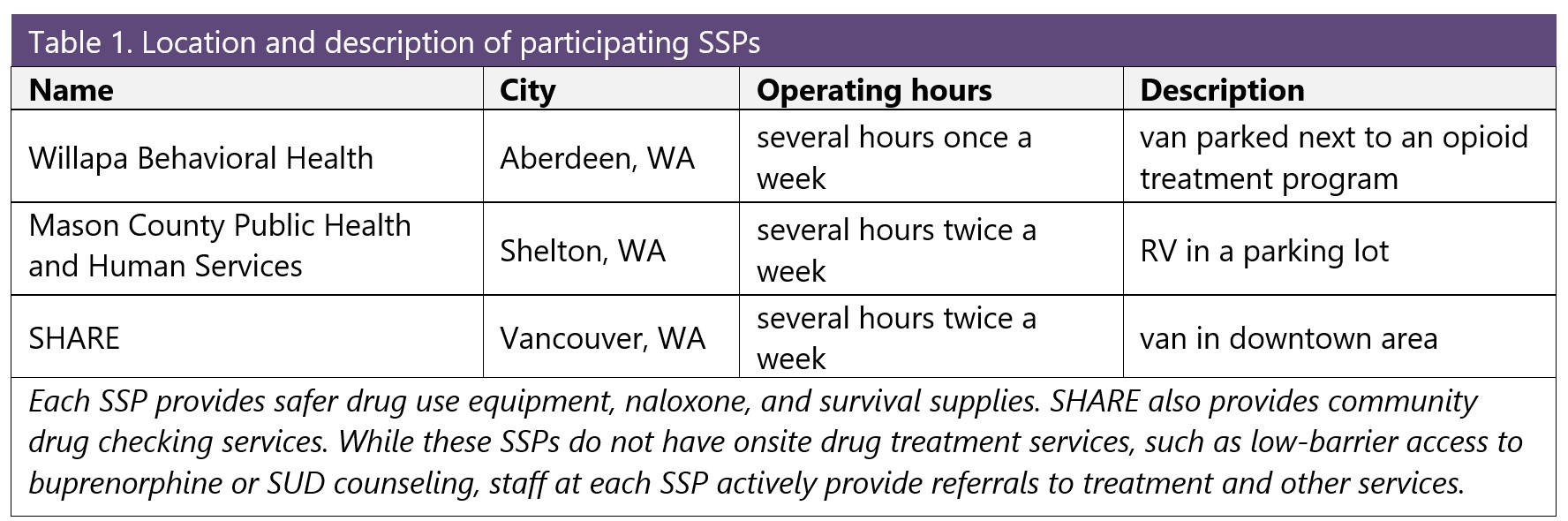

This descriptive study used qualitative interviews to understand experiences and perspectives of participants using both harm reduction services (at SSPs) and SUD treatment. Approval for this study was obtained from the University of Washington Human Subjects Division. Project partners included three SSPs in WA State that were selected for geographic variability and because they had not previously been involved in qualitative interviews with our team (Table 1).

Interviews were conducted during regular SSP hours in Fall 2024. SSP participants were eligible if they:

- had accessed SUD treatment in the last two years.

- had used non-prescribed opioids or stimulants in the past week.

- were at least 18 years old.

- spoke English.

“SUD treatment” was defined as any use of detox, inpatient or outpatient treatment, medication prescribed for opioid use disorder (i.e., methadone, buprenorphine, naltrexone) or recovery support/12-step groups.

Semi-structured interviews were completed after verbal informed consent was obtained. Interviews were recorded and transcribed by a HIPAA-compliant transcription service. Rapid qualitative analysis was conducted using transcript summaries and team-based thematic analysis (Hamilton, 2013; Hamilton et al., 2019). MaxQDA software (Verbisoftware 2022) supported the initial summary process. Data visualization was conducted in the R Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Core Team 2025) with the ggplot2 package (Hadley Wickham).

Results

Conclusions

- Participants appreciated easy access to SSPs, positive interactions with non-judgmental and caring staff, and the availability of essential resources that were hard to get otherwise.

- Benefits of SUD treatment included help to reduce or stop drug use, better coping skills, and reconnection with children/family. Many felt buprenorphine or methadone provided stability.

- Although harm reduction and SUD treatment have different approaches and intentions, the majority of participants felt these programs could be complementary; using both harm reduction and SUD treatment programs had substantial benefits.

- Participants expressed broad support for the cross-pollination of SUD treatment and harm reduction services. This included support for providing both types of services in the same location and for providing education about both types of services in different programs.

- People expressed interest in obtaining treatment and other services at the SSP because of the lower-barrier access.

- People endorsed expanding access to low-barrier and flexible programs where supportive staff could provide holistic care and offer supplies to meet basic needs.

Limitations

The majority of people we spoke with were unhoused, and their perspectives may not be representative of everyone who uses drugs. Our interviews did not ask about other services such as medical care, housing, legal aid, or other supports, although those issues arose frequently. Interviews were conducted only at vehicle-based SSPs where cohoused SUD services are not available. Perspectives may be different among participants of SSPs that do have onsite SUD treatment services.

The interviews collected for this study were gathered using purposive, non-random sampling and as such are limited in terms of their generalizability. We talked exclusively to people who were currently using SSP services, so the possibility of documenting negative experiences with SSPs, including discontinuation of SSP use, was limited by design. In addition, alternative perspectives from people currently in SUD treatment about their experiences using harm reduction services/SSPs was not a part of this study. Further research on these additional perspectives could contribute meaningfully to this area.

Acknowledgements: Thank you to the syringe services program participants who shared their time, expertise, and experiences with us. Your insights and knowledge are essential to guide the work to reduce improve the health of people who drugs.

Thank you to the syringe services programs who partnered with us on this project: Mason County Public Health and Human Services, SHARE Vancouver, and Willapa Behavioral Health. These interviews were possible thanks to the trust and positive relationships you have with your participants. We appreciate the work you do to keep people alive.

WA Health Care Authority funded this project and had no editorial role.